Exactly when the first motor scooter was produced and which vehicle should be awarded the accolade, is a subject of great debate. It is largely acknowledged that the first production motorcycle was the Hildebrand & Wolfmüller, a 1490cc (don’t get excited, it only produced 2.5hp!) powered two-wheeler from 1894.

But, as a scooterist, some look at the Hildebrand & Wolfmüller’s step-thru design and suggest that maybe the world’s first motorbike was in fact, a scooter.

From the beginning to major brands

The Auto-Fauteuil from France was first produced in 1902, and while accepted by some as a scooter, it was still a vehicle without a true designation – more of a car on two wheels. It lasted in production until the early 1920s, around the time of the first scooter boom of the 20th century.

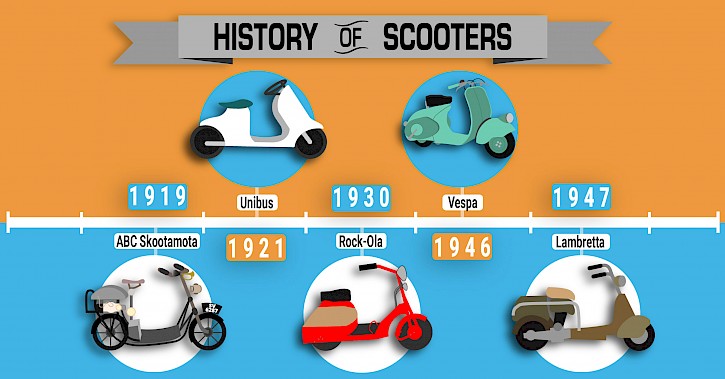

The design of early machines such as the Autoped from the USA (also licensed to be built in Germany and Czechoslovakia) looked a lot like today's children’s ‘stand up and ride’ scooters. While the later, British built ABC Skootamota of 1919 boasted a seat! As for style, the first scooter that we’d recognise as something similar to todays vehicles would be the 1921 Unibus, produced by the Gloucester Aircraft Company, which boasted legshields and bodywork protecting the rider from road dirt and the engine.

The next scooter boom took place in America during the 1930s with some truly stylish machines that looked towards both art deco and Buck Rogers for inspiration. The Rock-Ola came from the company of the same name, who are most widely-known for their Jukeboxes. Moto-Scoot was at one stage ‘America’s most popular’, while brands such as Salsbury, Powell, and Cushman emerged during this period and survived to continue after WW2.

After hostilities ended, industries around the world were looking to restart, with populations wanting to get back to normal. Cheap, affordable transport was a common theme, and this period saw heavy industry manufacturers like Honda and Fuji begin scooter production in Japan, for example.

It was the scooters produced in Europe, however, that really set the scooter scene as we know it today. Italian firms took the laurels, producing scooters with style for the masses that proved to be best sellers. Piaggio were once known for trains and aircraft, but, after the war in 1946, they began the production of the Vespa scooter. A product they continue to produce in Italy to this very day.

In Milan in 1947, industrial Innocenti produced their first Lambretta, which was to prove the big rival in Europe, as well as in many other places worldwide, to the Vespa.

Of course, other scooter manufacturers existed over the post-war scooter boom period. Many had backgrounds in motorcycle or bicycle production. Companies like BSA, Panther, and Dayton in England, Peugeot in France, and, in Germany, former aircraft manufacturers Heinkel and Messcherschmidt, joined in with bike companies such as DKR and Maico. While some of these were mechanically superior to the two Italian leaders, it was the stylishly simple Lambrettas and Vespas that the masses chose to commute to work.

Scooter Culture

From the very beginning of the post WW2 scooter boom, these ‘modern’ machines have starred on the silver screen. The 1953 film Roman Holiday, starring Audrey Hepburn and Gregory Peck, is arguably the most famous example of a Vespa scooter used as an inconspicuous form of transport for a princess in Rome. Of course, Piaggio were not going to argue with the free advertising for their Vespa scooter. It is believed that the film resulted in tens of thousands of sales for the Vespa in the years following the film’s release.

Scooters in general, albeit most commonly the hugely popular Lambrettas and Vespas, often made appearances in films and TV shows. Today scooter spotters will point out the Vespas in La Dolce Vita and Jessica, mention Debbie Reynolds and her Lambretta in the Singing Nun and will continue their list with American Graffiti, The Talented Mr Ripley and more recently, Larry Crowne.

It’s films like Absolute Beginners and Quadrophenia, however, that embraced the association of youth culture with the scooter. The latter, the most famous and arguably inspirational with regards to its impact on the Mod Revival movement.

The Modernist movement can trace its roots back to the late 1950s. Youths took it upon themselves to dress in smart, modern European clothing, drink coffee from Italian cafes in London, listen to Modern Jazz music, and a few, no doubt felt that the then modern European scooters fitted the bill when it came to transport. Fast forward a few years, and like all underground movements, this one had been hijacked by the masses. Its roots became diluted and adapted, and suddenly ‘Mods’ were the latest youth culture to attract young Brits.

The initial reason for the Mod movement’s association with scooters arguably echoes that of the post-war scooters creation in the first place; the need for cheap transport. By the early 1960s, there was an abundance of cheap, secondhand scooters on the market. They were cleaner and more stylish than many motorbikes of the time, which happened to be ridden by ‘dirty rockers’ anyway. For those with an ounce of style, the scooters complimented their continentally inspired smart clothing.

Fast forward to the late 1970s to Quadrophenia, a film produced by The Who. Based on their early 1970s rock opera album of the same name, the film follows the lives of young mods in the early 1960s. Quadrophenia launched in cinemas at the same time as mod revival bands, such as The Jam, The Lambrettas and Secret Affair and ska revival bands (mainly on the 2-Tone record label) such as Madness, The Specials and The Selecter hit the charts.

This mod revival period saw scooter-riding teens eventually morph into scooterboys. The 1980s became a melting pot for the (social) scooter scene it is today.

Rules and regulations

As much as I love riding with the wind in my hair, the reality of life makes it impossible. There are simply too many insects determined to take my eyes out. More importantly is the protection I need against street furniture and trees should I even take an unfortunate slide down the road.

On that note - the crash helmet was a piece of rider legislation that was not enforced until 1973. However, over the years a number of campaigns were launched in an effort to save lives by encouraging all riders of powered-two-wheelers to wear one.

Other rules have been set over the years as the numbers of machines on the roads grew. Brake lights (many scooters as recently as the 1950s didn’t have them as standard), speedometers, and more recently in the 1980s, directional indicators have all become compulsory.

Much of that makes sense really. Even the indicators, whilst not being great for the aesthetic of your scooter, do have their practicalities. Not least when riding at full throttle on a motorway and in need of changing lanes.

More recently however, regulations are being regularly introduced not simply for safety’s sake but also, to protect the environment. All new vehicles have to meet increasingly stringent rules regarding exhaust emissions and fuel consumption.

The fuel we put into our vehicles is also being changed to take in more eco-friendly additives. The current trend is to add an ever increasing percentage of bioethanol.

Bioethanol fuel is predominantly produced by the sugar fermentation process. The main sources of sugar required to produce ethanol come from crops grown specifically for energy use, such as corn, maize and wheat.

The problem with this ethanol – aside from the fact that it may damage certain components in engines - is that farmers earn far more money producing corn for fuel rather than food. This could see poorer countries suffering from food shortages in the near future should oil companies and legislators fail to address the problem. While tackling climate change is clearly an important objective, we must find a more sustainable way to do so.

Other regulations regarding pollution have seen rare minerals mined around the world to use in the production of catalytic converters, and yet all of this is arguably simply vote-winning tactics by politicians who want to be seen doing the right thing while also appeasing the large corporations that sponsor their party’s elections. The reality is that coal burning power stations, acres of factories and thousands of passenger jet aircraft cause far more pollution on a daily basis than road based vehicles. And as for those of us on Tarmac, scooters generally don’t cause traffic but simply filter through the jams.

There are of course a few regulations such as compulsory anti-lock brakes (ABS) on new machines over 125cc that do have their merits, but at the same time will also add a cost to the product that the end user must pay for. Could this not simply be dealt with by better road training for the rider and fellow road users maybe?

Two wheels better than four

If you’ve got this far then you probably don’t need much convincing and already ride a powered-two-wheeler. But just in case you don’t, here are some very good reasons as to why two wheels are better than four.

Many moons ago, after I left school aged 16, I worked in London. I commuted the 30 miles or so round trip by train. It took less than a year for me to realise I was better off on my scooter. Not only was the journey quicker each way, but I didn’t have to suffer the over-crowded underground, rude fellow passengers and their unsociable smells.

It was also cheaper too, although back then, Westminster Council didn’t charge motorbikes or scooters to park in their parking bays. Which made sense, as more two-wheelers could help to ease the pressure on our over-crowded public transport systems and congested roads. Most places in the UK and certainly in Europe offer free parking for two-wheelers, many with railings or other security devices to lock your scooter to.

Research published by the Trades Union Congress estimates that 3.7 million, or about one in seven, workers spent two hours or more travelling to and from work. A lack of investment in roads and railways is just one of the reasons being blamed for increased journey times.

Encouraging more people to travel by scooter could cut commuting times significantly. While traffic jams simply slowed me down, filtering past stationary cars in a careful, steady manner meant I still progressed along my way at a reasonable pace. You can of course carry a passenger if you’ve passed your test, which I soon did, saving us both money.

Should you wish to venture farther afield, you may be able to save even more. Toll bridges in England rarely charge scooters and bikes, and ferry fares are less than for cars. If you decide to head for the seaside in the height of the summer for example, I’d wager you could ride in and park in the town centre for free. In most cases it would take far less time than a car would spend in a traffic jam when heading towards a ‘park & ride’ a few miles out of town!

The last stop!

A less obvious bonus of travelling on two wheels is the camaraderie you’ll discover with fellow riders, and the freedom riding a scooter gives you. Escape your car and you will notice things you were oblivious to before. You’ll discover new sights and smells (some good, some not so great!) as well as new roads that in a car you probably wouldn’t have bothered with. These in turn lead to new places, new adventures, and a new way of life.

I’ve been riding scooters continuously for over 30 years now and have made more friends than I could ever have expected. I’ve ridden to places I probably never would have otherwise, saved goodness knows how much on fuel, parking, and time, and still look forward to every new adventure on my scooter.

Last but not least, if you have your very own scooter you need to insure, make sure to get a scooter or classic scooter insurance quote direct with Lexham!